In the digital age, our reliance on search engines for information retrieval has become nearly instinctive, shaping how we access, process, and consume knowledge in our daily lives.

It makes sense that we naturally use digital note-taking apps the same way.

I am here to tell you that relying on the search feature is robbing you of the most exciting part about using a zettelkasten: serendipity.

Niklas Luhmann navigated 67,000 main notes in his zettelkasten using an index with 3,200 entires.

He did this by listing only one to four locations where a keyterm was linked in his file. From there, any related notes could be quickly discovered by browsing through their internal connections.

You might think there is no reason to revert back to this old, outdated method of finding your notes.

I get it, search is fast. Sometimes instant. We have developed many years of muscle memory to pull up a search, type a query and press enter within seconds.

Searching often seems like the fastest way to retrieve knowledge, but what good is it when you aren’t sure exactly what you’re looking for?

Unlike the search feature, the index has another hidden advantage of reducing the cognitive load associated with information retrieval and organization. Instead of the starting point of note retrieval being your memory with a search, the starting point of the index is a list of entrypoints into meaningful connections of your ideas.

The index not only serves as a navigational scaffolding of your zettelkasten, it surprises you with your own knowledge.

Luhmann referred to his zettelkasten as a “serendipity machine” and “surprise generator”. To experience the zettelkasten this way, you must fight the urge to rely on search to find your notes.

One of the things that makes a zettelkasten so useful is its both rigid and fluid structure. To preserve this utility, we want to maintain a balance between the two with our indexes.

An index contains an organized list of links to notes relating to a category, topic or keyterm.

Not every note needs to be indexed. Since an index is an entrypoint, you want to point to the top level idea when it leads to a sequence or cluster of related notes.

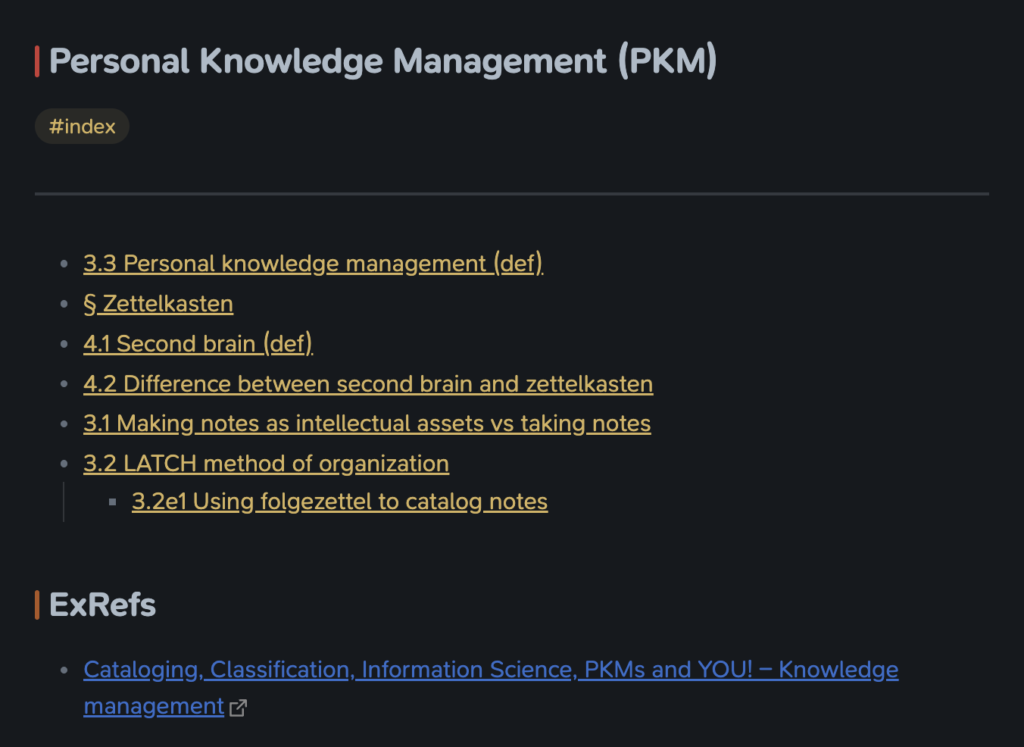

Here’s what one of my indexes looks like.

Notice how I am not using a more free-form MOC style list of links with headings and additional knowledge. It is just a straightforward list of links that take me to a top level idea where I can further explore the relationships that emerged from those notes.

The only heading I use is to designate ExRefs (external references) which are external links that I do not have filed inside my zettelkasten. I avoid category headings in my indexes because I am less likely to find a link if its organized under a category I am not looking for.

Similar to using a search, category headings for your indexes can actually add more friction and reduce the probability of serendipity occurring.

Allow yourself enough freedom to be surprised by notes you weren’t looking for but don’t leave any single note in a silo so it is difficult to resurface.

You will find a balance with practice.